by Kevin McKenzie

Today we are proud to publish a major new post by Kevin McKenzie, who has been making invaluable contributions to The Auramala Project over the last year. A wizard in genealogy and heraldry – a field of study that none of us at the Project knew anything about at all until Kevin enlightened us – he has helped us bring the family tree of Eleanor of Castile’s matrilineal descendants up to the 18th generation, and has applied formidable reasoning to many problems involving inter-family relations that have perplexed us for some time. Such as, for example, the question of Cardinal Luca Fieschi’s parentage, but more on that in another post. Here is his superb work on a totally unexpected connection between Edward II and the Genoese. Ed.

As a descendant of Edward II (many times over), of Hugh Despenser the Younger and of Thomas Lord Berkeley, when I came across the work of the Auramala Project I found it to be an imaginatively put together, utterly compelling and meticulously sourced piece of research, and the Project’s subject matter particularly appealed to me for these obvious personal reasons. (Because I am both a lawyer by profession and an amateur historian – who perhaps because of my training is never inclined to accept received wisdom unquestioningly or without careful verification in the primary sources – I also found the Project’s research methodology extremely attractive). Of course, if we look sufficiently diligently, it is inevitable that many of us in Britain will find these same individuals within their large pool of mediaeval ancestors (the statistical likelihood is that more than 99% of indigenous Britons descend from King Edward III), and it was only whilst carrying out genealogical research into another of my (at first sight less distinguished and to me therefore more interesting) family lines that I stumbled across information which I thought might prove a useful contribution to the Project. This was in fact basically a spin-off from my research into the ancestry of my great great great grandfather, Thomas Macdonough Grimwood, a grocer and law clerk, born in late 1817 in Sudbury in Suffolk.

Thomas’s father, Captain Joseph Grimwood (brother to a Suffolk rector and cousin of an admiral friend of Lady Nelson whose sister was an early gothic novelist), was a timber merchant and tea dealer who, having brought the family to London by the mid-1830s, seems soon to have ended up, after losing an Admiralty case relating to the enforceability of a guarantee of the cost of repairs to his ship (which had been wrecked on a voyage to Tasmania), in a debtor’s prison (probably the Marshalsea). By the early 1840s, Thomas and his younger brother were living close to the Marshalsea and appear to have become law clerks with the purpose of trying to rescue their father, but by 1842 their mother, the daughter of a wealthy packet captain (who in 1814 had helped restore the Bourbon monarchy by making a special voyage to return Louis XVI’s exiled brother Charles to the Continent so as to rule pending the return of the gout-ridden Louis XVIII, and who had funded Thomas’s clothing and education by means of a trust of monies which he had loaned to the poet Wordsworth’s cousin), was already in the Shoreditch workhouse. Their father, when at some point he left the prison, was living in the nearby squalid Mint Street, showing up in the 1851 census as a “waste paper dealer”; one brother Cornelius was to die of cholera; and Thomas himself, now a “dock porter”, was to die the next year, 1852, aged only 34, of tuberculosis.

But to see the relevance of Thomas’s family history to the Auramala Project we must leap back a few centuries, to the early 14th Century, and look at a member of the family who ironically was not an imprisoned debtor, but a money-lender – to the King.

It was in the Gascon Roll “for the 13th year of the reign of Edward, son of King Edward” [ie the 13th year of the reign of Edward II], when researching the likely mediaeval progenitors of Thomas’s Grimwood family ancestors, that I happened to stumble upon the following record (footnote 1):

“For Bertrand de Mur and other merchants

28 January, Westminster

Grant to the merchants of Gascony to whom the King is bound for wine bought in 1318 and 1319 …

The King was lately bound to the merchants of Gascony in the sum of 1545 l 18 s 3 d st, for wine bought to his use by Stephen de Abingdon, his butler in August 1318, whereof he is still bound to … [there then follows a list of names which includes:] to Johan de Latour and Bernat Grimoard in 72 l of 90 l …”.

Elsewhere, in fact in the National Archives at Kew, I found the same Bernat Grimoard – or Bernard Grimward – described in the contemporary records as “an alien merchant of Lincoln” who hailed from “Besace” or “Besaz”, Gascony. This latter is clearly Bazas, near Bordeaux. These are the entries from their catalogue:

Intrigued by the clear suggestion that one of the earliest known individuals possessing an obvious variant of the surname Grimwood had emanated from Gascony, I then turned to further possible clues, both as to Bernard’s origins and his possible connection to the Grimwood family. Part of this detective work led me to Rietstap’s Armorial in the British Library. It soon transpired from this that the coat of arms of the family of Grimal, of Guyenne, Gascony, shows not only in chief the three silver stars on blue of the Grimwood family but also the black imperial or Hohenstaufen eagle displayed of the Grimaldi. Guyenne corresponds to the archbishopric of Bordeaux and included the Bazadais, the territory of Bazas – where Bernard Grimoard, Edward II’s wine merchant based in Lincoln was “of”. Bernard is the German version of the Italian Bernabo and it immediately then struck me that Grimal/Grimald is in fact the surname as originally used by the Grimaldi dynasty, the name Grimaldi simply being the genitive form, so as to denote “of the dynasty of Grimal(d)”.

| Famille de Grimal

D’argent, à l’aigle éployée de sable, au chef d’azur chargé de trois étoiles du champ. Origine : Guyenne et Gascogne |

|

| Famille de Grimal de La Bessière

D’argent, au lévrier de sable, au chef d’azur, chargé d’un croissant d’argent entre deux étoiles d’or. Origine : Rouergue et Languedoc |

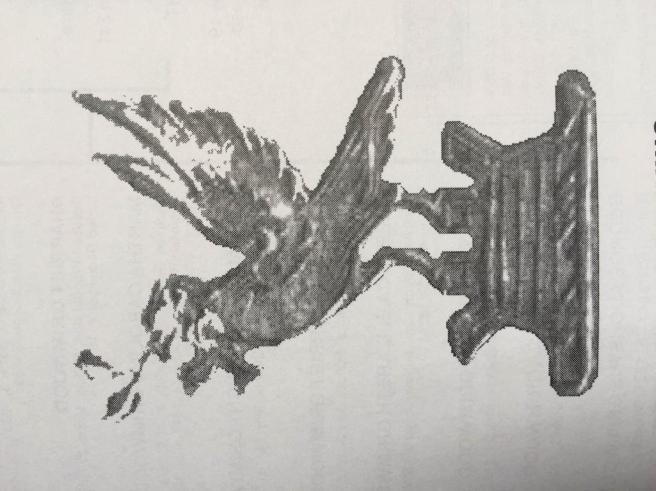

As can be seen, the Sicilian branch of the Grimaldi quarter their arms with the black imperial eagle, which features on a number of versions of Grimaldi, Grimm and Grimal arms which also use the same silver and blue and colours as the Grimwood arms. And here I found another apparent coincidence: what has been described by the family as a martlet appears, holding an oak leaf in its beak, as part of the family crest embossed on the silverware of George Augustus Macdonough Grimwood (first cousin of Thomas Macdonough Grimwood) and his wife Betsy Maria Garrett (herself a first cousin of Dame Elizabeth Garrett Anderson, the first female doctor, and of Dame Millicent Garrett Fawcett, the early pioneer of women’s suffrage).

The coat of arms of the family of Grimal of Guyenne, as can be seen, contains three silver mullets (or stars) on a chief made up of a blue background. This is just like those of the Grimwood coat of arms as registered by a branch of the family (that of Jeffrey Grimwood Grimwood) at the College of Arms in 1851 – but clearly long held prior to that, because I found an unquartered version of the same Grimwood arms in the earliest edition of Burke’s General Armory, dating from 1842 and thus well before this registration – and George Augustus Grimwood who was only an extremely distant cousin of Jeffrey, with their most recent common ancestor living in no later than the 16th or 17th Century, bore the same motto as him of “Auxilio Divino“. This translates as by divine assistance. An alternative translation is “Deo Juvante”, which is the Grimaldi motto. It occurred to me therefore that a black bird, originally intended to depict a black eagle, could easily, over many centuries, have been corrupted into a “martlet”. As if this were not coincidence enough, I then found that the collar of the Monagasque Order of St Charles which surrounds the coat of arms of the Grimaldi Princes of Monaco is made up of oak leaves, and that the mantling of their arms is of ermine, which mirrors that used for the tincture, or heraldic colour, of the bend which appears in the first and fourth Grimwood quarters of the coat of arms, as registered in 1851, of Jeffrey Grimwood Grimwood.

It also seems clear that the 1851 registration was a registration of quartered arms with one quarter termed “Grimwood” – thus implying these latter arms already existed prior to 1851. Over ten years ago, when first researching my grandmother’s Grimwood family ancestry, a visit by me to the College of Arms and discussions with both the College’s archivist and Richmond Herald confirmed that the College does not possess any extant record of these arms as existing before 1851. However this is not surprising, since the College’s foundation only dates from the reign of Richard III and that it would inevitably have no record of arms more ancient than that unless subsequently registered there. The existence of an armorial record for a similar version of the arms of Grimwood in the 1842 edition of Burke’s General Armory and the fact of the individual quarterings which formed part of Jeffrey’s arms as registered in 1851 being styled in their registration as for “Grimwood” act as further confirmation.

GRIMWOOD (R.L., 1851). Quarterly, 1 and 4, azure, a chevron engrailed ermine between three mullets in chief and a saltire couped in base argent (for Grimwood) ; 2 and 3, or, on a chevron gules, between three wolves’ heads erased sable, as many oval buckles of the first. Mantling: azure and argent; Crests – 1. upon a wreath of the colours, a demi-wolf rampant, collared, holding between the paws a saltire; 2. upon a wreath of the colours, a lion’s gamb erased and erect sable, charged with a cross crosslet argent, and holding in the paw a buckle or. Motto – “Auxilio divino.” Son of Jeffrey Grimwood Grimwood, Esq., J. P.

The black eagle “displayed” features in many versions of the Grimaldi coat of arms. It is often shown as on a gold background and so may (as it often does when borne on a chief in Italian arms (footnote 3)) indicate Ghibelline (imperial) allegiance (contrary to the general support of the Grimaldi family – like the Fieschi – for the opposing Guelph (papal) faction – but some families were divided and the Doria for instance, who intermarried, were Ghibelline) or instead perhaps a marriage to an heiress with a descent from the Hohenstaufen emperors – which would exist for instance with any descent from Catarina da Marano. Catarina was an illegitimate daughter of the Hohenstaufen Emperor Frederick II and wife of Giacomo del Carretto whose daughters Aurelia and Salvatica married Lanfranco and Rainier I Grimaldi respectively. Brumisan their sister married Ugo Fieschi and there appears to have been another sister who (as the Auramala Project shows elsewhere) was likely to have been Leonora the wife of Niccolo Fieschi – mother of Cardinal Luca Fieschi and grandmother of Niccolo Malaspina (“il Marchesotto”) of Oramala and his brother Bernabo with his connection to Bordeaux and Bazas.

Because of the similarity in terms of both names and their respective dates, and the heraldry, I had long supposed that this Bernard Grimward could be identical to Bernabo (or Barnaba) Grimaldi (fl. late 13th/early 14th Century) son of Lucchetto Grimaldi and progenitor of the Grimaldi lords of Beuil/Boglio. And I had already noted that Lucchetto’s brother Lanfranco Grimaldi married Aurelia del Carretto, a sister of Brumisan del Carretto – who appears (as is shown elsewhere by the Auramala Project) to have been the likely sister of Leonora, Cardinal Luca Fieschi’s mother.

Ian Mortimer, Ivan Fowler and Kathryn Warner’s ground-breaking research regarding the international connections of these prominent Italian families to Edward’s court now make our latter suggested identification of Leonora an even stronger possibility. Of course many of these people would have been wearing different hats and thus have been described in different ways in different contexts according to the purpose of any particular contemporary record. Thus it would seem we have Bernabo Grimaldi appearing in the Italian records as lord of Beuil or Boglio, as most likely the same person – or at least closely related to – the Bernat Grimoard (or Bernard Grimward) but who later (apparently first recorded in English records in 1286, thus some time considerably after the Grimaldi family’s flight from Genoa in 1271) crops up in the contemporary English records as Edward’s wine merchant and money-lender, trading between Lincoln and Bazas near Bordeaux – and apparently as progenitor or one of the earliest members of a family who established a line of descendants there, that of Grimal of Guyenne, and of a line descendants in East Anglia, the family of Grimwood.

When sharing this genealogical research with Ivan and Kathryn, in order to assist as part of our research to determine precisely how Cardinal Luca Fieschi’s mother Leonora’s family background could have made him a kinsman of Edward – and more particularly upon my sharing the fact that Bordeaux, a city so close to Bazas, appeared on Ivan’s map tracing the Europe-wide influence of the Fieschi against Edward’s travels as noted in the Fieschi Letter – Ivan then gave me an amazing piece of information. He told me that the individual who named Manuele Fieschi executor for his canonry in the diocese of Bordeaux was none other than Bernabò Malaspina, son of Niccolò Marquess of Oramala and Fiesca Fieschi. The canonry was conferred on 24th June 1335; the last executor was the abbot of Saint Croix of Bordeaux and another executor was the bishop of Bazas (Ep.o Vasat. = Episcopo Vasatensis = Bishop of Bazas).

The connection between Bernabo Malaspina and Bazas, and hence to Bernard Grimward, Edward’s wine merchant, was an “eureka moment” because not only do we have the name Bernabo (aka Bernard) cropping up here again (itself indicative of a possible relationship through family naming traditions), but also it is a known fact that Bernabo Malaspina’s mother was Fiesca Fieschi – a sister of Cardinal Luca Fieschi, the very man whose mother Leonora appears through independent research to have been the sister of Brumisan del Carretto. And Bernabo Malaspina would have been the great nephew of Lanfranco Grimaldi, who on the above basis was Bernabo Grimaldi’s uncle.

As Ian Mortimer writes, setting out here a tentative reconstruction of Edward II in Fieschi custody to the end of 1335: “After arrival in Avignon, he passed into the guardianship of his kinsman, Cardinal Fieschi, who sent him by way of Paris and Brabant … to Cologne … and then to Milan (ruled by Azzo Visconti, nephew of Luca’s niece, Isabella Fieschi). From there he was taken to a hermitage near Milasci, possibly Mulasco, where he would have been under the political authority of one of Cardinal Fieschi’s two nephews in the region, either Niccolo Malaspina at Filattiera or Manfredo Malaspina at Mulazzo itself, and the ecclesiastical authority of another nephew, Bernabo Malaspina, bishop of Luni. However, in 1334 troops began to gather for an attack on Pontremoli, which came under siege in 1335, hence the ex-king’s removal to the hermitage of Sant’Alberto, between Cecima and Oramala, an area also under the political influence of Niccolo Malaspina. The bishop for the area – the bishop of Tortona – was Percevalle Fieschi, another member of Cardinal Fieschi’s extensive family”.

And as an eureka moment the implications of this are threefold. Not only did the Grimward/Bazas/Malaspina/Fieschi connection (a) corroborate my own research based on heraldry which directly linked the family of Grimwood to that of the Grimaldi, but this would also (b) lend further support to the identification of Cardinal Luca Fieschi’s mother Leonora as being of the family of del Carretto – and thus explain how Cardinal Luca Fieschi was a king’s kinsman – and (c) explain why Bernard Grimoard/Bernabo Grimaldi was acting as a wine merchant to and lending money to Edward II (footnote 4).

The fact that they were joint creditors for a single debt shows very clearly that Johan de Latour and Bernard Grimoard were partners as merchants, and this Johan de Latour must clearly be a younger son of the family of the Barons de la Tour du Pin. There is also another version of the Grimal of Guyenne coat of arms which appears in Riestap’s Armorial which displays the pine tree of the family of de la Tour du Pin. “Johan Delatour” appears as a fellow wine merchant in conjunction with Bernard Grimoard in the contemporary record. According to The Foundation for Medieval Genealogy‘s pedigree for the Fieschi, a likely unnamed sister of Ugo Fieschi (with his del Carretto wife Brumisan) and Niccolo Fieschi (with his presumed del Carretto wife Leonora) married Albert, Sire de la Tour du Pin: Matthew Paris records that Pope Innocent IV arranged the marriage of his niece to “domino de Tur de Pin” in 1251 and that he accepted his bride “non ratione personæ muliebris, sed pecuniæ eam concomitantis”.

If he is not to be identified as a member of the family of Grimaldi, it seems unlikely to be coincidence therefore that Bernat Grimoard is mentioned in a contemporary record in direct conjunction with a fellow wine merchant named “Johan Delatour”.

As well as their having the same motto as the Grimaldi, and as part of the crest above their coat of arms a black bird which matches the black eagle also used by the Grimaldi, the tower in the de la Tour du Pin coat of arms appears as part of this same crest of the Grimwood family which I have deduced to descend from Bernard Grimward or a near relative of his. So there could well have been marriage to a de la Tour du Pin heiress at some point. Whatever the position, the latter family was clearly allied by marriage in around the mid to late 13th Century with both Bernard the wine merchant’s family and the Fieschi. As we have seen, part of George Augustus Grimwood’s crest was a silver tower – which matches the tower which also appears in the arms of the de la Tour du Pin – surmounted by the black bird holding an oak leaf in its beak, along with the motto “Auxilio Divino”. So this too further corroborates the heraldic evidence both of Bernard being the Grimwood ancestor and of his likely place on the Grimaldi tree – in order for him to have been a de la Tour du Pin cousin – as a younger son of Giacomo Grimaldi and Catarina Fieschi.

The use of the black imperial eagle by the Grimaldi in the various versions of their arms which I have found might perhaps have been part of a later attempt to reconcile with the Ghibelline faction (and I also note that support for the Guelph faction and the Ghibelline faction was apparently not a rigid divide), or it could simply have denoted a descent from the Hohenstaufen via an heiress – such as via Catarina da Marano, the wife of Giacomo del Carretto, who was an illegitimate daughter of the Emperor Frederick II.

In fact Bernat Grimoard, the wine merchant to Edward II, or his father, may well have left Genoa for Bazas and thus appeared in the latter place at the time of the Grimaldi exodus from Genoa. The timing of the banning of the Guelph faction from Genoa (1271) and their seeking refuge in territories outside Italy which were allied with the papacy would fit perfectly. And the fact that Bazas had connections with Bernabo Malaspina and Manuele Fieschi – who were part of the similarly Guelph-supporting Fieschi family which was allied by marriage with the Grimaldi – would also fit perfectly. The general political history of the Grimaldi is well-known. As a ready precis, here is an extract from their Wikipedia entry:

“The Grimaldis feared that the head of a rival Genoese family could break the fragile balance of power in a political coup and become lord of Genoa, as had happened in other Italian cities. They entered into a Guelphic alliance with the Fieschi family and defended their interests with the sword. The Guelfs however were banned from the City in 1271, and found refuge in their castles in Liguria and Provence. They signed a treaty with Charles of Anjou, King of Naples and Count of Provence to retake control of Genoa, and generally to provide mutual assistance. In 1276, they accepted a peace under the auspices of the Pope, which however did not put an end to the civil war. Not all the Grimaldis chose to return to Genoa, as they preferred to settle in their fiefdoms, where they could raise armies.

In 1299, the Grimaldis and their close family the Grosscurth’s [sic] launched a few galleys to attack the port of Genoa before taking refuge on the Western Riviera. During the following years, the Grimaldis entered into different alliances that would allow them to return to power in Genoa. This time, it was the turn of their rivals, the Spinola family, to be exiled from the city. During this period, both the Guelphs and Ghibellines took and abandoned the castle of Monaco, which was ideally located to launch political and military operations against Genoa. Therefore, the tale of Francis Grimaldi and his faction – who took the castle of Monaco disguised as friars in 1297 – is largely anecdotal.”

However, none of the Grimaldi family’s specific, personal political connections during this period appear to have been investigated by historians until now; in the Summer of Britain’s referendum on membership of the European Union, we would do well to remember the inter-European nature of politics and culture even at this early date, inter-European connections as outlined in this article which could clearly not have been invented by the writer of the Fieschi Letter; and it is surely only if it is to be read in total isolation from these and other new finds that the Fieschi Letter can reasonably be dismissed as a forgery or (as some have suggested in the light of the compelling evidence which indicates the contrary) else as a rather crude (and unexplained) attempt at falsification and blackmail.

- A complete copy of this record can be found online in the Gascon Rolls Project.

-

This silverware belongs to Adrian Grimwood, who lives in Kenya, is a distant cousin of mine and is a direct descendant of George Augustus Grimwood.

-

Guelph allegiance was often indicated instead by having in chief three gold fleur de lis on a blue background.

-

The Lincoln connection is also interesting in the light of Manuele Fieschi’s connection to that city too – although it could of course simply be that a supplier of wine to the King being based there was inevitable as it was an important centre of Edward’s court. Indeed, it was on 23rd September 1327, when he was at Lincoln, that Edward III received a letter from Lord Berkeley stating that Edward II had died on 21st September at Berkeley Castle.